After years on the road performing first with These United States and more recently with Vandaveer and The Mynabirds (among other bands), J. Tom Hnatow now calls Kentucky home. The multi-instrumentalist and producer/engineer is as eloquent about his craft as he is about his favorite poets. Here, he shares his thoughts on the connections we make through music and on why Homer’s Iliad is the perfect read for a band on tour.

J. Tom Hnatow’s nickname is “The Llama” (and his last name is pronounced like the intergovernmental treaty organization). A longtime D.C. resident, he’s now based in Lexington, Kentucky, where he’s a producer/engineer at Shangri-La Productions. He identifies pedal and lap steel as his primary instruments, but he’s also wicked good on guitar, dobro, and banjo. I recently chatted with Tom after a Vandaveer show.

By way of background, Vandaveer is the alt-folk project of Mark Charles Heidinger. Vandaveer tunes are by turns wry, jaunty, and wistful. My favorites are like a controlled burn of a fiery confessional — their structure and dynamic control an equipoise to the lyrical content of ceding control to the darkness.

In the band’s stripped-down incarnation, Mark sings and plays guitar while Rose Guerin offers up crystalline harmonies that imbue the songs with a haunting intensity. In studio and on some tour stops, Vandaveer’s sound is fleshed out with a rotating cast that includes Tom on pedal steel and Phil Saylor on banjo. I’ve written about their music before and I finally got to see the foursome live on an eve of the eve show (that is, on December 30th) at The Hamilton. I wish I could describe just how sublime it was.

To remark that the band’s sound is augmented by Tom’s playing is to barely scratch the surface. Though the capacity crowd was pressed hungrily against the stage, Tom rarely glanced out at the audience. Rather, his gaze was focused alternately on his bandmates and down at his instrument as he wove gossamer strands of sound, manipulating tones and textures — a sort of chiaroscuro — all subtle, altogether poignant.

Here’s a taste of Mark, Rose, and Tom at a Stone Room house show in 2013.

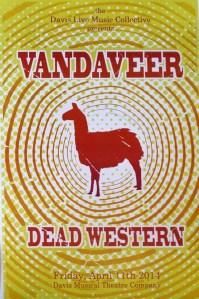

Adopting the narrative style of Homer, we begin the conversation in medias res. I asked Tom to share the story behind the llama tattoo. It all started with the Davis, California, venue hosting a Vandaveer show.

The [Davis] guy emailed and said, “We’ll give you twelve bottles of wine, and as a pre-show thing, you get to visit a winery, and we’ll give you food. So what else do you need on your rider?”

Mark, as a joke, said, “Well, actually, we need a petting zoo.”

The guy responded, “We can do that. We can do this thing — but, well, there’s not going to be any llamas.”

And Mark wrote back and said, “Oh, that’s alright. We have our own llama. It’s fine.”

So we get the poster for the show. It’s this beautiful silkscreen poster, and there’s this llama on it. And Mark said to us, “Welllll, that’s awesome.”

I was at the point where I was planning my next tattoo. I had it designed. And Mark said, “You should get this. Get the llama.”

It happened that the guy who did the poster is from Lexington [Mark’s hometown and Tom’s current home]. And I said, “We gotta do this, we gotta act on this, otherwise my willpower…”

So the next show we’re playing is in Portland. And at the show, this woman is sitting down in front furiously texting and we’re thinking, “God, this is really obnoxious.” But then she says, “I got you an appointment. Ten a.m. tomorrow.”

The next morning, I get the tattoo. If you’re ever tempted to get a tattoo at ten in the morning, hung over — terrible idea. First thing in the morning, before coffee, someone doing this [drums fingers on wrist]. It’s just — it’s not good.

So that’s how you became the llama?

Oh, no. No, I was the llama before. One does not simply get a llama tattoo if one is not the llama. I’ve been the llama for a long time.

Because of your gentle disposition? Or because you hiked the Inca Trail?

Neither of those things. Robby [Cosenza], These United States’s drummer [also of Vandaveer and The Fanged Robot], he gives people nicknames. They’re all just totally absurd. Like Mark, instead of Heidinger, his last name, it was Hi-din-gers [with a hard “g”]. So my first tour, it was three weeks long, and [Robby] said, “We’ll give you a nickname. It’s Tom Lllama Dingdong. That’s what we’re going to call you for three weeks. And it’s abbreviated TALADD.”

And it just stuck. And now it’s been secured by actually having it adhered to my body.

Well, it’s pretty great. And now for more “serious” questions. First instrument?

Piano.

Lessons as a kid? Under instruction of parents?

Not under instruction of parents, but — they forced me to play for ten years. I was six when I started.

“Forced.” So you stopped because —

They said when I was sixteen I could quit. So I did. Then my brother got a guitar, and I took it from him and learned to play it.

Was it the kind of music that you were learning?

Yeah, the classical training methods — I wasn’t that into it. It also makes me realize that as an adult, the thing that I value is socialization. The collaborative aspect [of music.] There’s none of that when you’re just taking piano lessons. I can’t bring my piano over and hang out. I didn’t know [at the time] that I could be in a band and hang out with my friends.

This was your older brother whose guitar you stole?

I have two younger brothers. I’m the eldest. He just wanted to play guitar. My parents got one for him for Christmas and stored it in my room. I picked it up and sort of figured it out. So I was three weeks ahead of him when he started [playing]. I already had lessons in piano so conceptually I had an idea.

He had no chance. [laughs] Then I got my own guitar.

Do your parents play instruments?

My dad’s a sax player. He was semi-professional. He’s a teacher, too — chemistry.

Did you ever go to his gigs?

Yes, all the time. I thought they were awesome. I loved going. He also did wedding bands and stuff. I always thought it was so cool — and it’s funny, people don’t have this anymore — I always loved the way his cases smelled. They smelled like cigarettes. That club smell — because back then, everyone smoked. And to me that was such a nostalgic smell. That meant you were a musician — because you smelled bad.

These dimly lit bars, people hunched over their glasses of whiskey, Smoking, listening to music.

Totally. And people don’t do that any more. When I get a case and it has that old cigarette smell — that, to me, that’s legit.

All the accumulated experience embedded, embodied in that.

Right, exactly.

So you were in high school around the time you picked up guitar. What kind of music were you playing?

Led Zeppelin, but really bad. [laughs]

Were you in bands in high school?

Yep.

Do you remember the names of the bands?

Yes.

Willing to share?

No. [laughs] The first band was called Sonos — Latin for sound.

The heavier band, more rock — was called Krank. We had no idea it was slang for meth. No idea. We were nerdy, ignorant suburban kids.

Were any of those songs recorded?

I recorded them on a little four-track. Sadly, it’s been lost to time.

That is sad.

Well, actually, it’s not.

So how did Krank morph into —

It didn’t. [laughs] It didn’t morph. Into anything. At all. I studied theater and philosophy. I didn’t study music. I just always played. When I lived here [in D.C.], I worked at a theater company.

Arena Stage, right?

Yes. I did graphic design. I always played music, but I didn’t think at the time that this could be a job. I played a lot and it was really only when I met Mark and that crew [of These United States] that it really took off. That was 2005.

What brought you from Pennsylvania to D.C.?

I had a bunch of people who I went to college with who worked here. They said you can get a job here. It prepared me really well. I worked as an intern for a year for twenty-five dollars a day. I learned a lot from that. How to live in DC on twenty-five dollars a day.

It’s useful not to start at a certain place. If you come into making a lot money, the idea of being an artist is foreign. It’s not that you never will, but it’s useful to be able to say: this is the baseline, and I can do this.

This touches on an issue that I’ve had heated discussions with friends about — making a living in music and the role of digital streaming in all that. Spotify, etc. Whether that model works. I’m curious what your thoughts are on that.

It’s new territory. It’s “here be dragons” stuff. Like on the old maps. It’s uncharted — we just don’t know yet.

I gave all my CDs away. I collect vinyl. I use Spotify. And I have a lot of digital files I’ll load to my iPod when I travel.

Every so often, there’s a piece about — well for example, there was recently a piece about how Pharrell’s “Happy” was streamed 43 million times but made him only $2700 in royalties.

It’s an evolving business model. Without getting into the technical details — there’s writer side, publishing side, and you can skew [the numbers] either way. Spotify will say, “Here’s how much we paid out.” Artists will say, “This is how much we were paid.”

But it’s a more complex metric. It’s also a bigger narrative. The tour [Vandaveer] did, the house concert, those are the rage. Everyone talks about the death of the CDs. But we sold tons of CDs on those tours.

Let me ask the question another way. How does digital streaming change how people support music, the arts?

I think it’s about interacting. Finding different ways to interact, whatever that means. Whether that means you go to a show. Or you buy show posters.

The deep, dark secret is that nobody is obligated to support art. It always has been difficult to make a living in art. It always will be difficult to make a living in art. It’s capitalism. If there’s something you think is awesome, and you’re moved to buy it — like, you bought the poster from the house show.

Does it matter to buy a CD versus iTunes? Not really.

You can separate fandom from capitalism. I.e., you can be like, I really like this band. I listen to them all the time on Spotify. It’s not making the band any money. You can still be a fan.

Before digital streaming, if you’re a fan, you actually had to purchase something. But now you can be a fan in a way that gives a band no more than a pittance. That’s new.

But we just have to adapt and be creative.

For Vandaveer, the house concert thing works. It’s a way to interact with people in a very intimate setting. Instead of three hundred people, it’s a hundred people or less. It’s intimate, it’s un-amplified. You’re there, you’re seeing everything that’s going on. For markets that you may not be as strong in, you can do it. For those shows, the host serves as the promoter. It’s very much more the European model. So you can play a market like Albuquerque. We don’t know anybody in Albuquerque. But it’s a Monday night and there’s a hundred people, and it’s awesome. And for mid-level bands, it works really well.

I guess the answer is, as an artist, you have to find ways to get people to interact with you. The onus is always on the artist. It should always be on the artist. If you’re not compelled to come to a show, then it’s not compelling enough. If you like Vandaveer, and you want to bring friends to see Vandaveer, that’s awesome.

Do you enjoy the experience of people coming up to you after shows, chatting? Is it a chore? Or does it depends on the interlocutor?

I don’t like talking about my pedal steel. The “how does that work” gets really old when I’m asked that every night. But then, I’m not really a social person. It does depend on the interaction.

The question people ask, which I think is funny, is, “Is it hard?”

I don’t know. As hard as any other musical instrument, I guess. Any instrument is hard. They’re all hard. Everything is hard. I don’t know. Could you do it right now? Probably not.

Or, “I want to get my kid one. Is it a good investment?” Absolutely not. It’s a horrible investment.

It’s like going up to a carpenter and say, “is it hard to build a house?” Yes. It’s like, “is that language difficult?”

I don’t want to sound like an asshole. Part of it is talking to people. That’s what gets people excited about house shows. That’s part of the appeal. It’s not in my nature to be a really extroverted person. But that’s part of what you sign up for.

Well, “is that hard” was not on my list of questions, so whew. [Here’s a 2009 video in which Tom talks about his pedal steel.]

I’m sure you know, of course, there’s an intrinsic compliment in that, in people wanting to talk to you. But what was it about pedal steel — why did you gravitate toward that?

Now, that’s a valid question.

[I smile. Tentatively.]

Look, the “is this hard” question — I get it. People want to talk and they’ve got to ask something, there’s got to be an opening gambit.

I always liked the sound [of the pedal steel]. I started on lap steel and dobro. I realized that I was doing more pedal steel type stuff. Approaches, bends, slants, and all sorts of stuff. So I thought I could buy a steel and get started on it.

It’s also good because in most towns, you’re the only pedal steel player. So, I love how it sounds and it’s easier to get gigs. I’m a good guitar player, but so is everybody.

It’s a supply and demand thing, in part.

Exactly.

And obviously I love the instrument. It’s also cool because it’s one of the newer instruments. It’s from the mid-50s. There’s a lot of uncharted territory, which is cool. We do a lot of stuff at the studio where we’ll really manipulate the signal and pitch-shift it down an octave and do ambient stuff. Less like, “here’s some country licks!”

I like your description [in an earlier conversation] of just jamming out with Phil [Saylor, of Stripmall Ballads]. Exploring the soundscape.

It’s a lot of what I get to do with Vandaveer. More soundscape-y. Some of the murder ballads are more defined but a lot of the Vandaveer music is more abstract.

The murder ballads collection is the first full-length that you recorded with Vandaveer.

Yes. [Mark and I] have always been friends and I’ve toured with him a lot, but that was the first time I did a full-length with [him]. But he works with Robby [These United States’ drummer] and with Justin [Craig, the other guitarist for TUS and currently musical director for Hedwig and the Angry Inch on Broadway].

For the next [Vandaveer album], it’s basically the band that made the second TUS record, except for Jesse [Elliot, TUS bandleader]. So it’s Robby and Mark and Justin.

Any estimates on when it’ll be out?

This year. Definitely in 2015.

Is there an album title yet?

Not that I can tell you. It’s not a hundred percent set. But [the album] sounds … it sounds like a band in a way the other records don’t — they’re more…

More stripped down.

Yes. And this is more fleshed out. It’s very big and very cinematic. Very different.

Any murder ballads?

No murder ballads. That was a one-off.

The interesting thing about murder ballads is that there are two types of people. There’s one type, the type that says, “Oh, you did ‘Pretty Polly.’” Everyone has recorded a version of that.

But then the cool thing is, other people are like, “Holy shit, I’ve never heard this song before.” And that’s the cool thing. To bring that to people who’ve never heard it before, never had that moment.

We all know the murder ballad. Rose [Guerin] comes from an old folk music family and she knows them inside and out.

They’re called murder ballads, but you play them at shows and people react and gasp and I think, “Of course there’s going to be a murder — it’s a murder ballad.”

But it’s so cool that people are hearing that for the first time, interacting in some way, shape, or form, having that moment of “Oh! Okay.”

It’s a different audience. And that’s really awesome. It’s cool to show people the stuff they may not have seen before. To curate that experience for them.

It’s interesting that you keep coming back to this idea of “interaction.”

I’m just stumbling on this right now.

But that is exactly what is so appealing — well more than appealing — to me, at least. what feels so necessary and vital about music.

Absolutely.

A way of making connections. Those moments. Discovering a new song, or a song that’s been around forever, but you’re hearing it for the first time.

Yes. And it’s also a bigger thing. It’s sort of like the locally-sourced food movement. People want that interaction. And the cool thing about going to a show is not always the show. The cool thing is meeting cool people and hanging out in a cool space. If people are like, “Well, I went to this show and I met this girl and that was awesome, fantastic.” Or, “I went to a show and I met a pedal steel player and I got to talk to him about his instrument.”

That’s the moment when people say, “I want more of that thing.”

Some of this is a realization I’m having right now. This interaction idea. What people want. I think people are sort of looping around to these carefully curated experiences. Maybe that’s me being optimistic. Which, you know, that’s a rarity for me. I sort of startled myself. [laughs]

First album you owned?

Billy Joel, Live in Russia. It was a gift.

First album you bought for yourself.

The very first was probably something classical. Mozart or something.

And then Def Leppard — I think Hysteria. I had to hide it from my parents. Had a friend buy it for me.

I actually saw Def Leppard a couple of years ago. Poison opened. It was…

I bet it was awesome.

Actually, it was. And there were a lot of mullets in attendance. Never seen so many in my life.

You know, I’ll stand by that band. We have discussions in studio [Shangri-La] of how much we like that band, overall.

First concert.

Don McLean. I was probably six years old. It was a free show that my parents took me to. Musikfest: A big outdoor music festival near Allentown.

If you were to identify records or artists who were influential to you at ages ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five?

The progression? When I was really young, I liked Stray Cats. Because I liked cats. That was really the entirety of the logic.

When I was sixteen, I got a Led Zeppelin box set and that sort of set everything off from there. It was a gift. My dad got it for me, which is weird because he hates that band.

When I was twenty, I got a Pavement record, which I came super late to. Where I grew up, there wasn’t the concept of indie rock, any non-mainstream stuff, or at least that I was connected to. So that was the birth of that.

And when I moved to D.C., I went to the Black Cat, five, six nights a week. Just obsessively.

And I was a huge, huge Deadhead in college. Serious Deadhead.

What music have you really liked this year? Besides the music you’ve worked on, obviously.

Good question. I listened a lot to that Spoon record. Obsessively.

And there’s a woman named Frazey Ford — she was in The Be Good Tanyas — she had a solo record called Indian Ocean that I really, really love. A lot of the band is the guys from Al Green’s band. So it’s serious soul, really cool. Those are the ones I’ve been obsessed with.

It’s been weird this year. I toured quite a bit and I’ve been so involved with work that I haven’t had time to just listen to music. On the drive up [to D.C.], I could just listen to music, and I had this moment: “Holy shit, I’m in the car listening to music, and music is awesome.” I had a rare moment when I wasn’t working, and was just enjoying music, which was cool.

What about favorite books or authors? Poets?

Oh man, I like a lot. Of all of those things. Yeah, we could talk about all that for days.

I love Faulkner. I love Dostoevsky. I went through a big period with Homer this year, The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Which translation?

The Robert Fagles translation.

He does a verse translation, right?

Yes.

That’s the way to go.

It is absolutely the way to go.

I like the Lattimore translation, too. I remember my very first class in college, the professor opened by reading The Iliad in Greek. And I was like —

Wow.

Yeah, it sounded so — well, musical.

If you’re touring, Homer is perfect: Where the fuck are we, and why do bad things keep happening to us? [laughs]

It also has one of my favorite quotes of all time in it: “Be strong, saith my heart. I am a solider; I have seen worse sights than this.”

Oh. Gosh, that’s —

Yeah, it helps a lot. In just about any situation.

I know you had all your stuff stolen in Tacoma [Washington]…

It wasn’t all. Just a lot.

Instruments?

No. We lost a lot of merch. I lost all my pedals and my cables. Rose lost a bunch of clothes. But no instruments.

And who else. Oh, Louise Glück.

The American poet.

Absolutely. Her newest book [Faithful and Virtuous Night]. Amazing. Astonishingly good.

And Rilke. Obviously Rilke. I got this thing which I thought would be stupid, but it’s mind-blowing. It’s a book called A Year with Rilke. It’s a daily reading. He’s so dense and it’s nice to have just a paragraph. Otherwise you’re deep into Sonnets to Orpheus and you think, “Oh, there’s so much in here.”

It’s been weirdly profound in a very beautiful way. It’s just really cool.

I had one of those moments with a Jack Gilbert poem recently. He’s not really as well-known. I came across a few verses about photography and poetry that captures, well — he says [I paraphrased it, and then looked this up]: “The photograph interrupts the flux to give us time to see each thing separate and enough. The poem chooses part of our endless flowing forward to know its merit with attention.”

That’s awesome. That’s really cool. Wow. I like that.

Favorite authors and poets — I would be remiss not to mention Samuel Beckett. That’s part of the fiber of my being. That bridged philosophy and theater for me.

Those are sort of the profound ones, I guess.

It’s a great list.

I tend to like male authors and female poets. Not wholly exclusively, but if I grouped them it would probably be 90-10 on either side.

What was the last book you read?

That’s a good question. I’m always reading, so — let me think. It was Richard Powers’ Orfeo.

Amazing. Really great book. It’s about this classical musician who decides to sequence DNA. And the FBI comes for him and he goes on the run. He writes so beautifully about music and the idea of finding order in the universe, and all in this tale of him becoming a more and more wanted fugitive.

It’s — this is a terrible description.

It’s an excellent description, actually.

The passages he writes about music — it’s like stop, put the book down, go find the piece of music he refers to, listen to it.

Many of my favorite novelists write in pretty profound ways about music. Haruki Murakami, for one. And I read Nickolas Butler’s Shotgun Lovesongs earlier this year. It’s supposedly based on Justin Vernon [of Bon Iver]. And there’s this passage about the way sunlight sounds. When a shaft of sun hits the aspens, it looked like a sound, a high-pitched note so pure, you could hardly keep your eyes open. The idea that the way something looks can also sound a certain way.

Like synesthesia. I think anything that makes you do that is pretty groovy. The idea that sound can make you think differently is a pretty profound thing.

[Music] is a sacred thing. I don’t say that from any religious place, necessarily. It’s wild to think that you’re performing and — I’m not moved by myself. That would be ridiculous. [As a performer,] you can be caught up in a moment and having fun. But to think on the other side of that, to think you have the ability to profoundly change people, in a major way, to set people off down these paths of — of whatever. Whether that’s, “I’ve never heard murder ballads and now I’m going to look them up.” Or something else.

I’ve had those profound moments as an audience member. And that’s a really special thing.

It’s primal. It’s a primal urge. You can’t help but respond. It’s fascinating. Like you instinctively realize that you’re listening to a song and bobbing your head. There’s a reason that’s happening.

How do you react to knowing that? When someone comes up to you and says, “This music changed my life. It got me through some hard times.”

On the performance side, I don’t think about that. It’s a different world. I just have so much to worry about. What song is next? Am I tuned correctly? Are all my things surrounding me in the correct pattern? It’s mostly: how can all this be moving as smoothly as possible so everything is going according to plan? Or why are things not going according to plan, and how can I fix that?

I think Mark would have a different answer. I’ve never been the front person. I’m always the supporter, the second person. It’s what I enjoy and gravitate toward. It’s my skill set. It’s why I’m a producer — the ability to augment ideas. Generally, I’m focused on what’s going on. On what Mark needs at a particular moment.

It’s weird when someone comes up to you. On the one hand, I want to be like, “Really? That?” Because it doesn’t ever feel that way from the other side.

Right. You don’t think, “I’m going to write the soundtrack for someone’s life.”

No — because that’s ridiculous and that’s pompous.

They asked David Gilmour of Pink Floyd what he thought of Dark Side of the Moon. It was the 40-year anniversary. And he said, “I don’t know, I’ve never heard it.” And that wasn’t a flip remark.

I can’t hear a These United States album without thinking: here’s where I was when we recorded that, here’s the head space I was in. Or, I remember playing this song in this town. I can’t emotionally respond to a Vandaveer song. I sleep in Mark’s basement when I’m here. I was in the studio when Mark recorded it.

I often hear people asking at the merch table, “Well, which is your favorite album?” It strikes me as a tough question to answer.

I actually like that question. I have favorites. Like the one — I’m suddenly blanking on the name. The one before the murder ballads. With the abstract cover.

Dig Down Deep?

Yes, Dig Down Deep. I like that one. It’s great.

Are there songs you particularly enjoy playing?

The murder ballads are fun — they’re looser. The Vandaveer music is more composed so there’s less winging it. It’s more like playing in a symphony. Good job. We followed the conductor. Didn’t screw up.

Tell me about tour life. What do you do on those long drives?

We get into this absurdist goofy stream of conversation. And you sort of develop your own language. This last year on the Vandaveer tour, we did this thing — I had Beowulf, the Seamus Heaney translation.

[Mark and Rose] made fun of me. So I read a paragraph and they were like, “Oh. That’s pretty awesome.”

So they made me read Beowulf out loud. And after that, we started Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Mark called it “Books on Tom.”

Of course when you’re hung over and all you want to do is sleep, and they say, “Oh do you want to read to us?”

No, actually. I sort of want to die. [laughs] But it was good.

Thanks for indulging me with answering all these questions. Anything else you want to add?

[laughs] I feel like I’ve pontificated enough.

Pontificating? Not at all. This was great — thank you. I really do appreciate it.

There is music inherent in language — cadence, tone, and so on. Chatting with a musician about his favorite poets was about as fun as it gets. To crib from the aforementioned Murakami, these are the moments that bring a warm glow to my vision and thaw out mind and muscle from endless wintering.

Check out Tom’s impressive discography here. I think you’ll agree — most industrious and creative llama ever. Ungulate researchers, take note.

* * *

Lately, I’ve been musing over the way in which a song that is a musician’s very personal creation becomes a shared vessel of meaning — listeners pour into each song their own heady cocktail mixed of dreaming and despairing. And I reckon even the most patient of musicians gets a bit weary of smiling politely at strangers who remark: oh, this song must be about such and such.

I don’t try to guess at the back story, but I do think that the music of Vandaveer has this preternatural ability to tap into our collective unconscious and draw out those shadowy creatures of regret and longing, and in so doing, loosen their death grip on us.

What also hooks me on Vandaveer is their ability to sculpt words and contour idioms as easily as if they were modeling clay — to make music that activates both the cerebral and the primal parts of our being. (I think “Spite” is a good example of this.) These musicians are pretty darn special, and I’m very much looking forward to their next album.

Vandaveer’s website is currently under maintenance, but check out their videos on YouTube and get their music on Bandcamp or iTunes.

5 thoughts on “Of pedal steel and poetry: A chat with J. Tom Hnatow”